Tyler Johnston on helping farmed animals, consciousness, and being conventionally good

An interview

This post is part of a series of six interviews with members of the effective altruist community. We talk about how they chose what to work on, and how they relate to doing good more generally.

Tyler Johnston is an aspiring effective altruist currently based out of Tulsa, Oklahoma. Professionally, he works on corporate campaigns to improve the lives of farmed chickens, and is interested in cause prioritisation, interspecies comparisons, and the suffering of non-humans. He’s also a science-fiction fan and an amateur crossword puzzle constructor.

We talked about:

his work on The Humane League’s corporate animal welfare campaigns

how he became a vegan and animal advocate

whether animals are conscious

how being conventionally good is underrated

On his work at The Humane League

Amber: Tell me about what you’re doing.

Tyler: I work for The Humane League. We run public awareness campaigns to try to get companies to make commitments to improve the treatment of farmed animals in their supply chains. This strategy first gained traction in 2015, and was immediately really powerful. Since then, it has got a lot of interest from EA funders.

Amber: Did The Humane League always do that, or was it doing something else before 2015?

Tyler: It was a long journey; The Humane League’s original name was Hugs for Puppies

Amber: Aww, that’s very cute!

Tyler: Yeah, I feel like we’d be a more likeable organisation if we were still called that. They started doing demonstrations around issues like fur bans, and other animal welfare issues there was already a lot of energy around. They then switched to focussing on vegan advocacy, which involved things like leafleting, and sharing recipes and resources.

Amber: So the strategy at that time then was to encourage people to go vegan, which would lower demand for factory farming, which would mean there were fewer factory-farmed animals?

Tyler: That’s right. There was some early evidence that showed this was promising, and it also just made sense to them, since most vegans would attribute their own choice to be vegan to a time in the past when they heard and agreed with the arguments. So they thought, ‘why wouldn’t this export to other people?’

Amber: But you said the strategy is different now - it’s to lobby actual food producers to treat the animals that they’re farming better. Say more about that.

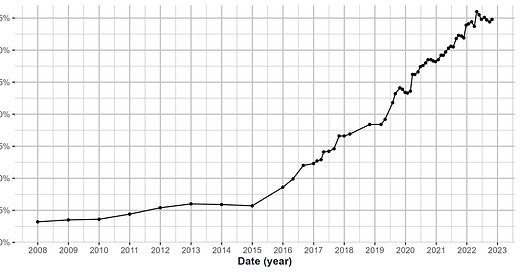

Tyler: That’s our dominant strategy now, yeah. It’s part of a broader shift in the [animal advocacy] movement toward institutional change rather than individual change. If for some given company, you either have to change the minds of, like, 10 million consumers, or a dozen executive stakeholders - the latter is just a lot more tractable. It started with running small campaigns to persuade companies to source cage-free eggs, and it turned out that this worked. Around 2015 there was a sharp turning point in the number of farmed birds that are cage-free - before 2015, the percentage was growing very slowly, from 3% to 5%, but between 2015 and today, the percentage went up from 5% to 36%. And people attribute this to corporate campaigns.

Graph by Samara Mendez: data available here

Amber: How does The Humane League persuade companies to do this? Do you appeal to their moral sense, or do you appeal to more instrumental reasons?

Tyler: We start by just reaching out to companies and letting them know that welfare reforms are an option, and that there’s good evidence that their customers really want this. There's also just obvious ethical reasons: raising hens in battery cages for eggs, for example, is deeply problematic. So we do a long pattern of outreach. And eventually, if that fails, then we launch a public awareness campaign. And those campaigns tend to be very effective because the majority of consumers agree with us. 94% think battery cages are unacceptable when they learn how little space the birds are given.

For these campaigns, we use more traditional methods, like public demonstrations and sharing information on social media. People write op eds that get published in the local paper, and we use all sorts of strategies to raise awareness. These campaigns tend to work, because once you increase the costs associated with bad PR to a sufficient level, it just becomes cheaper for a company to implement the reform. And once you have a credible threat, you can export that to other companies. You can say ‘look what happened to your competitor when the public found out about their supply chain practices’. And then it’s cheaper for them to avoid the campaign even starting, and just make the reform. And then suddenly, you have hundreds of companies making commitments.

Amber: That is quite a good strategy: with one campaign against one company, you can actually influence many companies, because they don't want the same to happen to them; you're changing the economic calculus for them. So it's cheaper for them to switch to cage-free overall, even though that's more expensive.

Tyler: Yeah. A lot of it is about building a reputation, because we want the threat to be credible. So we want it to be clear that we're completely relentless and passionate, and this is a problem that won't go away for them. If that threat wasn’t credible, then it'd be very easy for them to brush it off.

Amber: What does your role as a Communications person involve? Do you write content? Liaise with people in the industry?

Tyler: Both. I’m on the team that does corporate outreach, so it’s more like business-to-business communications. I try to really hone our outreach to stakeholders and improve our authority and expertise in the area. They often have very specific, nitty gritty questions about stuff like ‘what it would take to implement one housing system [for farmed animals] over another? Does this standard actually improve welfare compared to this other standard from the National Chicken Council, which has a lower set of standards than the one that we promote?’ And so it's really trying to be as effective as possible in direct communication with a select few people at these companies.

Amber: So who are the people at the companies that you are talking to? Executives, logistics people?

Tyler: We definitely want to connect with the decision-makers as much as we can, though this isn’t always the CEO - it could be the supply manager for a certain region, for example. More and more big companies now have a Chief Sustainability Officer, and these are often interesting allies: it seems to me that these people are often really, really interested in pushing the company to be better - and the company wants that, and hires them to do that. An interesting insight from my work is that there are a surprising number of companies that are not opposed to animal welfare reforms.

Amber: So when they do make reforms, it’s not solely profit-focussed - there is some genuine desire to make the world better?

Tyler: That's right. I heard a story that one of our team members was in a meeting with an executive at a major fast food chain, and the executive cried on the call, and said, ‘I didn't know this was happening, I didn’t know our birds are being treated like that’. A surprising number of people are receptive to the ideas. So I try to make compelling resources to change their mind before the public awareness campaign begins.

On becoming an animal advocate

Amber: How did you get into this type of work? What were you doing before?

Tyler: This is my first job out of college. As an undergrad, I studied English literature (which is a less common background for EAs). When I first started college, I wanted to go into music; then I shifted to English literature and was interested in journalism for a while. I think my interest in The Humane League grew out of exposure to EA in college, and some interest in animal advocacy before that.

I had a summer internship at the Good Food Institute, researching the investment landscape for alternative proteins - I’m not sure if that was a great fit for me, but I learnt a lot. This role at The Humane League made a lot of sense to me, because it leveraged my experience of writing and some of the skills I picked up in my degree programme, and applied that to the work that I wanted to do: direct work improving the lives of farmed animals

Amber: It does make sense that that would be a good fit for your background. Is it fair to say that you prioritise animal welfare, out of all the EA cause areas?

Tyler: To some extent. A lot of it is personal fit. It’s something I'm really passionate about, and I have some useful skills that can push the movement forward, so that makes it the right answer for me. If I suddenly became a grantmaker overnight, and I had to make decisions about what to fund based on my true ethical commitments, it would probably be a kind of diversified portfolio across many cause areas. There probably would be a lot of longtermism and AI risk, probably a plurality of the money. But given where I am right now, and where I could be: what's my comparative advantage? And what do I really want to be working on? That’s animal welfare.

Amber: Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. You said you had some interest in animal advocacy before you were aware of EA. How did you get interested in that?

Tyler: I definitely was not always an animal lover. I, like many people, grew up in a meat-eating household and a culture where [veganism] wasn't very common; but less commonly, my dad was also a hunter and a fisher and outdoorsman, so I did a bunch of that growing up. I was kind of on the opposite end of the spectrum; I killed animals and didn't think much about it. Actually, something felt very cosy and familiar about those things.

Amber: Yeah - it was what you were growing up with and the norm in that company or culture.

Tyler: That's right. I actually think about that a lot, because people in the animal rights space will sometimes say, ‘The only reason that we're okay with factory farming is because the suffering of the animals is happening out of sight. For the consumer, they're just walking into a grocery store where they see this ground beef that doesn't look like an animal, in this clean shrink-wrapped plastic container. They don't realise that there's an animal behind it.’ And I think that that's probably not true.

Amber: Yeah - people do hunt, and are fine with killing animals directly.

Tyler: Yeah, and all around the world people raise their own animals and then slaughter them. So I think there is something about our treatment of animals that is a lot deeper than just cognitive dissonance or distance from the animal to our food.

Amber: Sometimes people who eat meat say things like ‘factory farming is bad, but it's a different situation if you're treating the animals well, with respect.’ Do you think that makes hunting and fishing feel better to people: they do have a level of care for the animal, even if they ultimately end up slaughtering it?

Tyler: For many people who practise some small-scale form of farming around the world, I imagine that's true. But I don't think it's necessarily true. My experience with fishing was just fishing for sport. And there you're just like, impaling a metal rod through the soft part of its flesh for fun.

Amber: So when did you start questioning that worldview and caring more about animal rights?

Tyler: It wasn't till I was in high school. I read an interesting book about consciousness by a cognitive scientist called Douglas Hofstadter - I am a strange loop. It wasn’t profoundly impactful for me overall, but what was impactful was a couple of footnotes or asides, where Hofstadter is like, ‘By the way, this theory is part of why I’m vegan’.

Basically, Hofstadter suggests this “cone of consciousness” idea: even animals who we might say are less intelligent than humans, seem to have very similar neural mechanisms to us. If you think that the basis of consciousness is physical processes in the brain and nervous system, these similarities suggest that animals could be experiencing consciousness like us, to some degree. And that was enough for me to start questioning: why would I expect animals and humans to have substantially different experiences? And I didn't have good answers.

So in this “cone of consciousness”: humans are the most conscious, and a cow is less conscious, and a chicken is less conscious, and a fly is less conscious… But today, I’m not even sure that that’s true. I can imagine that one way of being conscious is having the visceral present experience of qualia; possibly humans, with our very advanced brains and intelligence, are able to filter some of that out in a way that animals can’t.

Like, here’s a thought experiment I like: if I had to insert a papercut as an additional event at some point in my life, would I rather add it today, at twenty-three years old, or when I was five years old? I think I would rather add it today, because when I get a papercut today, I just flinch for a second but then ignore it and keep doing whatever I'm doing. But when I was five, I’d really be wrapped up in it and it would dominate my experience for ten minutes; I’d be crying and thinking like, ‘this is the worst’.

Part of me wonders if this big prefrontal cortex that humans have lets them refocus on other things, and filter out the visceral experience of pain, or see that there's a purpose behind it, or that it won't last forever. Whereas maybe kids and animals just have the physical experience, and they have no sense of why it’s here or how long it will last, or that there's anything else worth thinking about.

So the book got me thinking about those sorts of things, and there’s many theories of consciousness where it doesn’t even look like animals have less of it - it could be that animals have more of it.

Amber: Yeah, that’s really interesting. There’s the raw experience of pain or pleasure, and then there’s how you respond to it, and I think the extra intelligence can go either way. Humans get into mental holes that non-human animals possibly don’t get into. But also, we have tools to respond to pain in ways that can make it less bad for us.

Tyler: Yeah. So after reading the book, I tried going vegetarian and I didn’t think much about it after that - I was vegetarian on and off. Then in college, I became more committed through maybe a mix of exposure to EA, and having sat down and watched one of these documentaries that show shocking footage of what happens on factory farms. I looked into it and discovered that those shocking practices aren’t rare; they’re industry standard; and at a certain point I was like, ‘Okay, I should actually find out how important this is, and adjust my life accordingly.’ And that led me to then go vegan, and eventually pursue a career in the field.

Amber: This is kind of a personal question, but how do your family feel about what you do, given that they’re a hunting and fishing family?

Tyler: I guess we just don’t talk about it that much? They’re very supportive, so I think I could do just about anything and I would have their approval. My dad definitely doesn’t agree with me, but it doesn’t put up major walls between us. I’m lucky in that way — in some families, it can be a much more difficult choice to make.

On cause prioritisation

Amber: You said before, if you were a grantmaker and were in charge of lots of funding, you wouldn’t put all of it into animal welfare causes. Do you see yourself continue to work in the animal advocacy field, or do you think that maybe in 5-10 years you might work in another EA cause area, or a different type of thing entirely?

Tyler: I think, barring any radical changes in my values, I see myself staying in this cause area. It’s hard for me to say how much of this is because of personal fit, vs ideological differences between longtermists and myself about what I should be prioritising.

Amber: To the extent that it’s because of ideological differences, what does that mean?

Tyler: Well, I think one thing is I probably have more of a suffering focus ethics [than many EAs]; I just tend to think that avoiding suffering is really, really important. When we’re considering whether it’s good or bad to bring potential beings into existence, there’s a big asymmetry between how I feel if they’ll predominantly experience pain vs if they’ll predominantly experience pleasure. If they’re going to mainly experience pain, it’s very obvious to me that it’s bad to bring them into existence, whereas if they’ll experience pleasure, it’s not obvious whether it’s good or bad - it feels more neutral to me whether they exist or don’t. So that negates some of the draw of longtermism for me: it makes me a bit more concerned about preventing the creation of beings that will suffer.

Then I’m probably also more sympathetic to broader democratic conceptions of EA that are less “fanatical” and are more aligned with what people outside of EA also see as good. Factory farming is really on the border there, because on the one hand, people eat animal products, and it's kind of the status quo. But on the other hand, people aren't okay with it. Pretty much all consumers, when they see images and videos [of the insides of factory farms] are like ‘I don't want that, and I don't want to support that.’ There's this one survey of Americans where they asked ‘Would you vote to ban factory farming?’, and 49% said yes!

And so it’s a weird borderline [area] I think, where there’s a lot of progress to be made. It’s a tractable way to align the world with what people both within and outside of EA want to see.

Amber: Yeah: banning factory farming is in accordance with most people's values. If you could offer them a way to have less factory farming and less animal suffering that wouldn't inconvenience them, most people would be like, ‘Yeah, sure’. Whereas with some things, they might not even want it even if it wouldn’t inconvenience them.

Tyler: Yeah. And it’s not to say that those things aren't important, but one of the most effective ways to build concern for groups that don't normally receive concern - one of which might be future people - would be to do really broad coalition building for people who are eager to expand their moral circle and to question their beliefs and practices. Working against factory farming could create moral circle expansion, and that could lead to more energy and excitement for x-risk, which is much less intuitive to people, I think.

Amber: It would lead to that through them having generally expanded their moral circles to include more beings?

Tyler: That's right.

Amber: Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. So those are some ideological differences. You also said that personal fit is an element. I'm interpreting this as something about passion or enthusiasm and motivation rather than skills, because it seems to me that communications skills could be useful for many causes.

T: I think about it as both passion and skills. I definitely have more passion for this. But also, in longtermism, a lot of the energy is around research. Communications skills are very important for my work because we’re creating campaigns that we’re sending out to the world. For things like AI risk and pandemic risk, there are a select few people like Will McAskill and Toby Ord who’ve written books that are getting the arguments out there, but I don’t know if it would be useful for there to be a public outreach campaign, like people sharing things on social media like “AI risk matters!” I don’t know if we’re ready for that.

Amber: Yeah, that's a good point. It's not just communications; there's a specific kind of communication you're doing that’s its own thing. And it's not as prominent in other areas.

Tyler: Yeah. I think some communicators are needed in longtermism, but maybe it’s only a few people who account for most of the impact there; whereas with animal welfare, there's such a big movement that we really do need all the help we can get from effective communicators.

Amber: Okay, so the personal fit thing is somewhat about skills.

Tyler: Yeah. I also think I’m better than many EAs at code-switching between EA spaces and non-EA spaces. Even the general animal advocacy movement, most of the people I work with every day, aren't EAs, and maybe actually have strong disagreements with EA. It's useful for me to be able to jump between those worlds - the vegan world, the EA world, and the broader public world. And I think AI risk isn't quite ready for taking that step out.

On being conventionally good

Amber: Is there anything important that we haven’t talked about yet?

Tyler: One belief I have that’s less typical among EAs is: doing conventionally good things is underrated. It’s good to do this as a form of self-signalling, and to make sure that your values are aligned with the world. I try to do good in many ways that aren’t exactly EA-aligned, or at least EA-maximised.

Amber: What are some examples?

Tyler: In college, while I was involved in EA stuff, I was also working for a homeless shelter. I think some of my friends would say, ‘does this really make sense? It's costing you a lot. You're putting many hours a week into it.’ And in my mind, it obviously did. But I think many EAs felt like that wasn’t the case, that I could be doing something potentially more impactful with that time.

Amber: So why did you feel that you got something out of that, or that it was important?

Tyler: The idea of self-signalling mattered a lot to me. I come from a very privileged background, and I also have a lot of opportunities to live a really comfortable life - for example, I could easily find myself in a high-paying job that is bad for the world. But I think trying to live in a way that viscerally affirms a commitment to others is really underrated. It changes the way that your psyche is and operates. I think it's valuable to regularly practise foregoing some personal comfort for the sake of realigning yourself with your values and trying to alleviate suffering in a direct, felt way. I worry that value drift is more likely when you are only doing research or very long-term projects that, even if high-value in expectation, you’ll never really see come to fruition.

I also pursued non-directed kidney donation for these reasons. People say that that doesn’t check out if you’re trying to maximise wellbeing. But I think, especially for longtermists, it’s really valuable to combine the work you do with also having a tangible impact on the world…like, there’s someone who’s not on dialysis [because of me]. This is probably a psychologically powerful thing, and it might make people more motivated to pursue their abstract research projects.

On moral offsetting

Amber: What do you think of moral offsetting: for example, with regards to animal products? Some people say, ‘Well, I could be vegan, but it's very cheap to buy offsets, which apparently alleviate the same amount of animal suffering. So I will do that instead of changing my diet.’ What do you think about that?

Tyler: This is connected to the self-signalling issue, and also to moral demandingness: I run into this problem, because I do buy into the offset arguments to some extent. I think the logic basically works out. It's plausible to me that the value of my being vegan ends up at something like $10 a year. And I’m a bit of a picky eater, so to maintain my diet, I buy things like Impossible meat, and I have plant-based milk in my coffee, and I might have the more expensive vegan option at a restaurant… So over the course of a year, I probably pay $100-400 more on food as a sort of “vegan tax”. So if I could counterfactually have donated that money to animal charities, would my going vegan be like going one step forward, twenty steps back?

But I think it’s important to live in a way that accords with the outcomes that you want, to make sure that you don't have value drift over time. And also, part of the value of veganism is symbolic for others, because you're showing that it's a valuable and doable thing. If I never knew any vegans, I never would have gone vegan. So part of the expected value of me being vegan is that in the future I'll meet someone, and we’ll talk about it. And they’ll be like “Oh, this person thinks that we treat animals really badly, and he’s vegan”; and then they'll meet you and be like “Oh, you’re also vegan, and you also think this is bad”. After they’ve met five people who think this way, they’re like “ok, maybe there’s something to it”. This person might then become vegan themself, whereas if I was just offsetting, maybe they never would have.

Amber: Yeah, I think I’d find it hard to not be vegan and do moral offsetting instead. It would just feel a bit unaligned and weird to me. Also, maybe part of this is that we don’t have to live an extremely morally-demanding life. If you’re allowed to have nice things generally, you’re allowed to have Impossible burgers - just like if you weren’t vegan, you’d probably eat some luxury animal products as well.

Tyler: Yeah, I think that’s the most sensible response. As I’m starting my career, I'm testing a version of the Further Pledge, which is just choosing an income that you're happy with and having that, and donating everything above that threshold. Then you don't have to think about it anymore. I think that this is something that more people should probably do. They don’t even have to choose a very low income: if you choose $30,000, you’re 95%-percentile wealthy across the globe or something, and you could set it even higher than that. It’s just so that people don’t have to think about trade-offs or offsets so much. You can stop thinking about whether it’s okay to buy the Impossible burger: if it fits within your personal spending budget, you can buy it.